MICHAEL COOMBS

The Faintest Idea - Michael Coombs

Dr. Emmitt Brown has a lot to answer for. I mean if it wasn’t for him I doubt I would be here, scrawling notes onto the pages of a very dog-eared notebook in a motel room in Green River, Utah—the predawn light creeping in from behind the torn mesh that partially covers the void left by the open windows, and the rumbling of the trucks pulling into the gas station over the road only just audible over the whirring of the ageing and fairly ineffective air conditioning unit hanging from the wall provide the backdrop, the liminal space that is at the heart of this trip. With a slightly fuzzy head, the result of the previous day’s long drive followed by a few too many of the state’s specialty beers,i and very little sleep, I head out into the burgeoning day with a backpack full of camera kit.

Despite, or maybe because of, the technological advances in the decade or so that has passed since digital photography became the default choice, it was very clear that this was a trip to be documented on film. In this case, a whole stack of 120 roll film that had been sitting on my bookshelves for many years waiting to be either thrown away or, as was to be the case, to provide the warm yellow cast that Kodak film many years past its ‘process by’ date gives to a road trip across the USA.

So what of ‘Doc’ Brown? Back to the Future, for some of us of the right age to see it in the cinema or in the following years on VHS, it was our first experience of the idea of an historical America, or at least the first to catch our attention. Alternating between a polished vision of California in 1985 and a beguiling image of mid 1950s America complete with its combination of classic cars, ‘vintage’ fashions and rock ‘n’ roll in a setting of romanticised conservative cultural values and a steadfast belief in the bright new future it brought this idealised vision of an historical America to life.ii

While there are certainly many more influential experiences that have intervened in my life in the last 25 years that have brought me here, from my school art teachers and university lecturers to the perennial influence of Kerouac, Gregory Crewdson, David Lynch’s The Straight Story, or even The Hold Steady, at the root of it there is still a bit of a Hill Valley tint to my sunglasses.

Destinations and Transcendence.

When the idea of this trip was first mooted I wasn’t clear as to its purpose, yet I made some decisions about where, when and how it would take place. I deliberately chose not to have an itinerary, just a car, a few dollars for fuel and some food, and the open road. While I felt it had some kind of connotations of pilgrimage it didn't pertain to what most people understand as pilgrimage, secular or otherwise. It didn't have a shrine or holy site as an end; it was, in essence, petrochemical wandering. However, following a brief period of research I embarked on the trip as a pilgrimage which, to my mind at least, had a precedent in the wanderings of the early Celtic Christian Peregrini who would also leave their homelands for destinations unknown.iii (MacFarlane, 2007)

It is often noted by prospective peregrini that the choice of pilgrimage was not a conscious one, but more that it selected them. Indeed this was certainly a notion with which I felt an affinity. While I had no final destination to focus my attention, it was clear to me that for a real road trip, America, or rather the United States of America, to distinguish it from it northern and southern continental counterparts, was the only conceivable location.

So what was the attraction of the USA? In the absence of any first hand experience of the nation beyond some brief acquaintances made while travelling in other parts of the world it was clearly based on the idea of America, its image a culmination of 30 years worth of exposure to its history, culture and mythology through the media of film, television, literature, music, advertising and consumerism. This America is as much an amalgamation of Back to the Future and Twin Peaks as it is a vague recollection of the principles of the founding fathers, faded monochrome images from the era of the pioneers or the gold rush, or scratchy TV images and sound bites from the Apollo space programme. I was adamant that, in its origins or aims, this trip was some kind of pilgrimage despite the absence of an obvious final destination or traditional object of veneration.

A common theme in discussions as to what differentiates a pilgrimage from any other form of travel often refers back to the idea that a pilgrimage is simultaneously an outward and inward journey, a journey toward some kind of a greater understanding of God. It’s an interesting problematic when discussing the idea of secular pilgrimage. With what can we replace this fundamental characteristic that is allied to a secular understanding? One response is that it is self-selecting. It is in effect, that upon which we deem important enough to impart that status of pilgrimage; however, this seems too circular to be the whole answer. It would also be obtuse not to consider the notion that these secular excursions are not pilgrimages at all, rather just another, albeit more directed, more personally significant form of tourism. This suggests that an acceptance of a religious context as being fundamental to the notion of pilgrimage, for many the obvious response to this is that, without religion or faith, we cannot have a true pilgrimage. While this may be true, can we not also have an experience that while not religious performs a comparable function? Perhaps a more analytical view is one that draws us back to the notion of religious pilgrimage as a form of sacrament, an outwardly visible sign of an inward grace, an idea that we can transpose onto a secular understanding. To explore this we need to answer the question of what pilgrimages are for; for me at least, there seems to be some kind of answer in an understanding of how the brain works.

The Faintest Idea

We are told that as humans we tend to privilege language in the sphere of meaning, we return to words not only to negotiate the everyday world around us, but that we also tend to resort to words to discuss art and music through a complicated web of semantic linguistic signs and frames. While this may initially seem illogical, it is understandable in the context of the developments in neuroscience and linguistics proposed by Charles J. Fillmore, George Lakoff or Antonio Damasio, who state, and I hope I’m not doing them a disservice here, that a linguistic system of frames and metaphor are hardwired into the way that the brain operates. While sitting in a motel room somewhere to the east of Denver on a humid afternoon in August, I came across a lecture by George Lakoff on one of the myriad of cable TV channels that, in-between tornado warnings for the local area, discussed cognitive science and the role of linguistics in American politics. The ‘ordinary conceptual systems’ that we use to negotiate the world that he described fitted closely with my thinking about how I understood pilgrimage and indeed America. Lakoff tells us:

“The brain is structured on frames and conceptual metaphors. Framing is normal. You can’t think anything without a frame, and every word is defined relative to such a structure.”iv (Lakoff, 2008)

I have never been completely convinced by the notion that knowledge is inseparable from naming, that in broad terms the function of labelling and categorising is comprehension; however, implicit in Lakoff’s statement is the notion that frames can exist independently of language, but all words operate relative to a frame. Wittgenstein shows us the problem of trying to speak about the things that can only be shown. He leaves us with his famous last proposition in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”. (Wittgenstein, 2002, p.89) This highlights the difficulties we have when explaining how we can have ‘ideas’ that are used to make decisions and understand the world, yet we have no real way of communicating them except through art. It is however clear that through the process of labelling we link to the frames that are essential to greater or clearer understanding. By this process remote locations or obscure ideas become tangible. To quote Robert MacFarlane: “Naming was and remains a way to place space within a wider matrix of significance; a way, essentially, to make the unknown known.” (MacFarlane, 2003, p.191) To me it seems that although we may need to name to give us the ability to discuss things, would it not also be true to say that to experience something either first hand or perhaps even vicariously, through dramatic retelling or emotive imagery, gives us another, a greater, level of understanding? With our first forays away from the planet in the early 1960s and later when Neil Armstrong first stepped onto the moon in 1969 ‘space’ became quantified in our imaginations, just as the Antarctic had with the ‘capture’ of the south pole by Roald Amundsen and Robert Scott in 1911 and 1912.

Could it be then that a pilgrimage is the process by which we manifest the transcendent or at least give it some frame of reference by which we can describe and understand it? Whilst naming gives us the ability to discuss the tangible, when we come to the a priori transcendental (in the Kantian sense),v we might think that this realm of self-referential frames would merely lead to circular arguments.

We can say that the notion of a God, defined by his absence (and subsistent faith in his existence) is transcendent. Most of us have had no demonstrable first hand experience of that which we call God. So how do we deal with this absence? How can pilgrimage bring us closer to God? It could be argued that through the act of pilgrimage we provide a 'frame' that goes beyond language but in which the word ‘God’ finds a greater meaning or significance.

If this system of frames is at the heart of how we all think, we are continually evolving our understanding of a myriad of seemingly unrelated concepts through experiences and gained knowledge. Relative frames and the meaning of words are in a subtle but continual state of flux driven through our actions: personally, socially, nationally and globally. However while these connections are in a sense fluid, intense experiences or repetition render the synaptic links that are triggered as permanent fixtures in our brains:

“Neural connections get stronger the more they are used, and you get certain ideas in your head that won’t go away, ever. The brain gets structured.”vi (Lakoff. 2008)

A pilgrimage is a way of making a series of loose ideas or connections physical, real, there to be drawn upon when we trigger a certain memory. When I choose to recall the straight black line on the Bonneville salt flats that demarcates the edge of the Southern Californian Timing Associations’ ‘long course’, stretching over the horizon on the rock hard intricate, interlaced web of startlingly bright white salt crystals and the specks of dust and debris around which they have formed, my mind retrieves the disparate elements of that experience from different parts of the brain. The sight of the day-glow red mile markers and the aroma of ethanol, gasoline and hot engine oil merge to reconstruct the experience. The brain recombines these separate elements in to a cohesive memory or recollected experience. This operates so well in fact, we are told that there is currently no real discernible difference between how we think or imagine and how we recollect;vii memories can be brought back together and ‘experienced’ again or drawn upon in part to help build up an idea or scenario you have never encountered.

Part of the memory recollection process seems to include Concept Neurons, an old idea that has until recently been dismissed. However, Francis Crick and Christof Koch, as part of their research into the neuronal correlates of consciousness, have examined activity patterns of single neurons in the hippocampus. These neurons are triggered by very specific visual stimuli. The interesting discovery is that these neurons trigger not only at, say an image of a movie star but also at the text of their name. They are triggered by the concept or idea of say Steve McQueen rather than just his image. In some cases neurons were triggered when a subject closely related to the first was shown, for a fan of Mr. McQueen’s work, the sight of a Porsche 917 in Gulf livery may also trigger the McQueen neuron yet a 917 in a different livery, one not seen in his 1971 film Le Mans, may not. These neurons demonstrate a basis for associative conceptual thinking in memory.

Yet although this extremely complex transfer of ideas and information is achieved through textual language it seems to me that the knowledge obtained through language, and therefore a second generation link to a frame, can not give the kind of full understanding that doing something in physical actuality gives us. We all know from experience that we learn better by doing rather than watching or merely being told. This is the essence of how pilgrimage operates as a means of learning; it is essential to the process of understanding the more obscure, less tangible ideas about who we are or what we do.

It is also interesting to look at the role of mirror neurons here; although there is still some debate as to their role in humans, it is generally accepted that these trigger when you perform an action or when you see someone else perform the same action. These mirror neurons are connected to the emotional regions of the brain, the result is we experience much of what we see happening to others. Firstly this is a biological basis for empathy, but it is also, importantly for this text, that they impart upon us an emotional synergy with those who we see engaged in a familiar experience. It is not a huge leap to suggest that the feelings I experience speeding along the more remote sections of the American road network come in part from my perceived experience of the characters in road movies from Vanishing Point to Two Lane Blacktop ... and maybe somewhere in my pre-motor cortex there is a neuron firing, one that relates to an old man riding across Iowa on a lawn mower to see his sick brother.

So where does this take us? In summary it would seem plausible that a function of pilgrimage is to put an experience into a frame, to strengthen the links between certain concept neurons, or to tap in to, and understand first hand, an experience we have only previously negotiated vicariously through a range of media from word of mouth to film. We can draw upon these events to give us a more succinct description of a loose set of ideas that can make up a relationship with an absent God, or whatever our secular pilgrimages lead us to, modifying a frame that will change the brain and therefore the way we think, — and who we are. Macfarlane was correct: naming something does make it real, but we have to go there to understand it.

Contradiction Games

In the process of trying to understand what this trip was about, I played a game where I would select two ‘things’—sometimes words, places, people, films or ideas: one that I felt had an affinity to the idea that I was pursuing in the process of this trip, the other—something related to the first thing, but was somehow unconnected. For example, this trip was San Francisco; it was not New York. It was Christopher McCandless; it was not Steve Fossett. It was Mulholland Drive; it was not Blue Velvet. It was faded shabby motels; it was not hotels. Through this process I documented innumerable, sometimes obscure relationships between contradictory images or ideas, what I would later understand—thanks to Mr. Lakoff—as linguistic frames. I had built up an image of what it was I was trying to explore.

This process felt appropriate when considering the USA as a nation of cultural contractions, of entrenched traditions and an unwavering desire for progress, of community and individualism, freedom, and a kind of Tocquevilleian tyranny of the majority, of religion and hedonism, of individuality and of belonging, yet unlike much of the Old World, here it is a sense of belonging with, or an attachment to, a piece of paper: A nation whose raison d’être was carved out with pen and ink, rather than from a common ethnicity, or the seemingly infinite historical lineage to a specific geography found in the Old World. However, it can be argued that a nation founded on an ideology is one prone to a degree of vulnerability. To know what America stands for, or rather why it is different, one must know and understand its origins. This is a unity of shared citizenship, but increasingly it appears the nation is looking inward towards it’s differences rather than to its unity.

One thing that I was unprepared for upon my arrival in the USA, was the number of flags, the omnipresent star spangled banner on car bumpers, t-shirts, or flying from every conceivable location. If you are anywhere but the remotest locations you would have trouble going 50 yards without coming across one. What were they all for? Was it in case I forgot where I was? Or was it—as the people I spoke to would have me believe—a symbol of a genuine sense of pride at being American and of the things for which it stands? To an outsider whose national flags are only really seen on public buildings, tourists’ postcards and for a few weeks every four years during the football world cup,viii its ubiquity gives a sense that, much like an overly elaborate apology, it is somehow trying to cover up, or rather to compensate for something.

Like most national flags the stars and stripes are a symbol or frame for the history and the ideology of a country, and in this case its uneasy overemphasis a symbol of the inherent fragility of its foundations in a simultaneously increasingly global society, one that is retreating into non-geographical communities of shared ideology or interest. However, one of the many benefits of having a national foundation born not of historicism but of design, is that the Constitution seems to have given rise to a kind of sense that if you can create a nation and its ideology, it’s certainly possible to create your own personal future and to have a chance of secular immortality though the greatness of some special endeavour. This has long been intrinsic to the American model; yet possibly more interestingly, from my experiences on this trip, it also seems to me that in some way it has lead to the notion that it’s also possible to construct your own history, a kind of personal historical revisionism. Idealised histories are part of the American identity, from Elvis, or the Abner Doubleday Cooperstown story, to the products of the film industry.ix While scholarly historical revisionism is regarded as part of the ongoing dialogue between the past and present that makes up the subject of history, there is a non-academic, even personal variant that is in itself, by no means unique to the USA but that is somehow embraced here to an even greater extent than elsewhere. This, from my own perspective as an art practitioner and—dare I say it—a romantic, is a fantastically alluring attribute. Where else can one make his or her own past, present and future to suit his or her own ideals and aspirations to such a degree? Something, I’m sure Doc Brown would understand only too well.

Road Trips

Travel can mirror this flexibility of perspective; it can give us a freedom from the mundane, the situations in which we can, not necessarily intentionally, fictionalise events and make our myths. Here all our normal frames of reference are no longer there to rely on. From a social anthropologist’s perspective an essential part of travel is the entering of a liminal state where normality is suspended for a given period. This liminal condition is a transitional state in which common rules of social behaviour are relaxed or even deferred. In these situations we lose the greater part of our social identity and status; we become exposed to ambiguity and indeterminacy. The product of this is not merely to take a break from the structures that we impose on our daily lives: it performs an additional function, even in the case of the American road trip, these experiences of difference and ‘other’ offer a situation against which we can question and reinterpret the normal. Although it is clear that not everybody while traveling away from ‘home’ is cognisant of this condition and likely to make a conscious effort to reevaluate their lives from this detached position; nonetheless it

This is a function of separation that many people experience regularly, consciously or otherwise, through travel. It can be argued that contemporary art takes up a permanently liminal position of its own, operating from outside the conventional, where it also gives us the opportunity to examine more closely and to reappraise the situations presented to us. In this way art not only highlights the subject separated from normal frames of reference, but also provides deeper insights into our own hermeneutical interpretational process. This was interesting when considering my view of America.

My America

The America I found was, as expected, an amalgamation of my idealised America, rich in melancholic nostalgia of filmic landscapes, abandoned semi-derelict motels and gas stations on deserted dusty desert highways, of billboards, hamburger joints, and of small town bars where satellite sports TV is always on.

In my head it was predominantly constructed of the romanticised fifties America, portrayed in Back to the Future, mixed with remembered passages from On the Road first published in the late summer of 1957, through the Marlboro cigarette advertisements seen in my grandparents copies of National Geographic, pictures of Craig Breedlove’s Spirit of America as featured in my picture book of racing cars, given to me for some birthday in my formative years, to the overly colour-saturated film of the build up to the launch of Apollo 11 at Cape Kennedy, as it was then, and to footage of skateboarders in empty Californian backyard pools that inspired me as a teenager.

I was standing in the middle of a sun-baked road, watching the warm late summer sun sink behind the Rockies through the viewfinder of the super8 camera I had borrowed from a friend for the trip, while the celluloid rattled through at 24 frames per second, when it occurred to me that this journey, far from having no real destination, was really a pilgrimage to an idea: the idea of America. It took the form of a series of micro pilgrimages to destinations previously unknown to me, yet they were all too clear when I found them. These places, chanced upon while meandering through this vast nation, were locations or experiences that fitted with my idealised America, those which reinforced or enhanced my myth.

This project explores this ideal of America. A pilgrimage to Dean and Sal, Neil Armstrong, Christopher McCandless, Marty McFly, Kowalski and the road as a raison d’être. It is the culmination of 30 years of received Americana and a period spent exploring how the myth fits and modifies the experience of the reality. It is detached from any global credit and banking crisis, while $100 plus barrels of oil only make it feel more poignant. As the idea of America as a land of plenty, providing for and protecting its citizens indefinitely draws to a close, it is at this point that nostalgia for this endangered epoch increases in vigour. Whilst this project explores my America, the pervasive nature of American culture will have left its imprint on most; the language of accompanying images will be readable to all. The path followed by Kerouac has become the foundation for many voyages of self-discovery, and On the Road is a manifesto and inspiration for quasi-rebellious road trips throughout the world. In the text, Kerouac’s alter ego, Sal Paradise, mirrors the ‘search’ of modern pilgrims, but in an untouchable pre-lapsarian golden age that epitomised this epoch of accelerated achievement, where the notion of frontiersmanship and freedom were reflected in bright chromium.

This trip and the resulting photographs access this enduring vision of the USA built as much on idealised histories as an appetite for a better future, and employs it as a foundation for an analysis of the function of constructed histories and borrowed nostalgia in the 21st century. So, the outcome of this investigation? It occurs to me that what a pilgrimage is really about is making manifest a sense of identity, a scene of what an individual considers fundamentally important: a physical tribute to somewhere, something or someone who may be long past, but yet we feel there is something in their character or achievement that reflects something of ourselves, or rather something of our idealised self, a statement of what one considers important directed more to ourselves than to others. It is through this process that we manifest the transcendent or at least give some frame of reference to it, through which we can describe and understand it. It gives us a tantalising grasp of some vital qualia. As a result the electrical pulses that join the various regions of my brain, the ones that give us our best guess at what makes up the marvel of consciousness, the ones that make me, me, are transformed in some permanent and physical way by these experiences.x

Notes to the Text

i. If you are ever in Utah and see a bottle of Squatters Full Suspension I implore you to try it. At the guidance of my friend Adam ‘Tex’ Fine, the exploration of regional specialty beers would be a theme we would continue across the myriad of states we passed through.

ii. It is interesting to note that we are now approaching a time where the date that Back to the Future was released is as distant to us as the 1955 Marty visited was to his native 1985. Yet somehow 1985 does not yet seem to provide the same scope for similar cultural reconstruction or cinematic historical revisionism.

iii. According to MacFarlane, R (2008) The Wild Places, Granta. p.23-26

iv. Lakoff, G, Politics of Language, 2008, US Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) television broadcast,August 2008

v. “I call all cognition transcendental that is occupied, not so much with objects, but rather with our mode of cognition of object insofar as this is to be possible a priori” Kant, I, 1998, Critique of Pure Reason, translated by Guyer, P & Wood, A W. Cambridge University Press. p.149 (A12.) and Passim.

vi. Lakoff, G, Politics of Language, 2008, US Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) television broadcast, August 2008

vii. Asdiscussedin:Schacter,D.AddisD.(2007) ‘The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: remembering the past and imagining the future’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. May 2007

viii. While I nominally consider the Union Flag to be my national flag, I include the St George’s Cross here in reference to England’s football team.

ix. As has been widely cited in the press including: Birnbaum, M. (2010) ‘Texas board approves social studies standards that perceived liberal bias.’ The Washington Post, 22nd May 2010. Historical revisionism has been shown in a slightly less benign form. Recently conservative elements of the Texas Board of Education approved changes to its history curriculum and textbooks to fit with Conservative moral and political motivations. It was proposed that Texas state schools would omit Thomas Jefferson’s philosophical influence from ‘world history’ lessons as well as the principle of the separation of church and state. Instead classes should teach that the founding fathers intended America to be a Christian nation. Changes will also emphasise the role of key conservative people and groups including Ronald Regan and the Moral Majority and the National Rifle Association.

x. As discussed in Massimini, M. Ferrarelli, F. Huber, R. Esser, S.K. Singh, H. and Tononi, G. (2005) ‘Breakdown of Cortical Effective Connectivity During Sleep.’ Science, VOL 309, ISSUE 5744, pp. 2228- 2232. The team examined the brain’s response to small, targeted, electrical pulses during waking and sleep. They found that under waking conditions the pulses triggered in one region of the brain quickly spread around various other regions of the brain, yet while unconscious these pulses only initiated local responses.

Contact

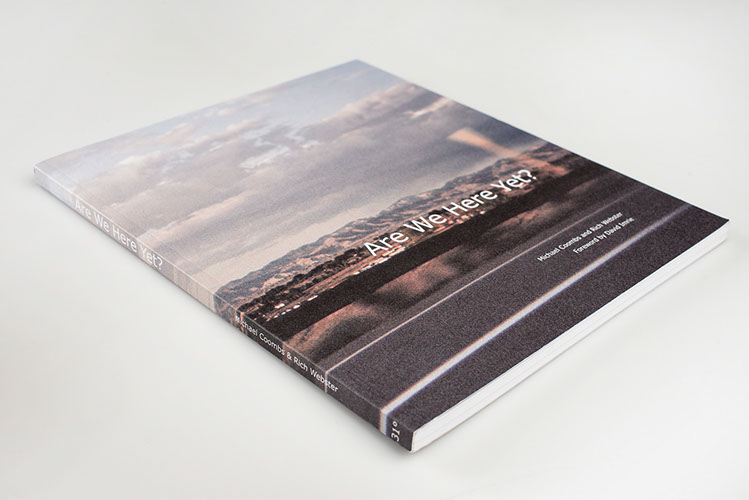

Available to order from Amazon.co.uk